Language learning in Malaysia: assessing the impacts of policies and planning

Language learning in Malaysia: assessing the impacts of policies and planning

Language planning is seen as an effort, usually at the national level, which is geared towards changing the language behavior of a given populace for an implied objective (Kaplan & Baldauf, 2008). As noted by Kloss (1969, which was cited in Cooper, 1989), the focus of language planning is corpus planning and status planning. What is implied by corpus planning is creating new forms, modifying existing ones, or selecting alternative forms of written or spoken languages, while the focus of status planning is on a national government recognizing the position or importance of a given language over the others (Cooper, 1989).

From a general view, language planning can be seen as a coherent effort made by individuals, groups of people, or organizations geared towards influencing how language is used or developed in a given area (Robinson, 1998). Therefore, language planning plays a pivotal role in any given country, with special reference to a multi-lingual nation like Malaysia. For instance, there are situations where people from different language groups compete to access the daily life mechanisms in the country, including education. Thus, it is vital that both the government and educational institutions work hard to equitably and effectively meet the demands of the populations in a way that the groups varied in linguistic repertoire are accorded an equitable opportunity to participate in governance and are also provided with the numerous benefits of such governance. In language planning, the basic decision is to meet these needs by limiting the linguistic diversity, and as such, leads to instances where a single language is declared the official language of a multi-lingual nation. Referring to Malaysia again, Bahasa Melayu (Malay Language) is the national and official language, while English is the official language in cases where a single variety of language is declared "standard" in order to ensure that linguistic unity is promoted in the country with its divergent dialects (Napisah, 2017).

In any case, records have it that in today’s economy, the success of any given country (including the overall development of the country) depends on the country’s skills, knowledge, and competencies. As a result of this, the Malaysian government has undertaken numerous economic policies, such as the 1st to 9th Malayan plan, with the intent of increasing the country’s socioeconomic status. Following these policies, there was a recorded increase in the per capita income to RM26, 175 in 2010 from the 2000 position of RM13, 939 (Laporan Kualiti Hidup Malaysia, 2011). However, not much reduction has been recorded in the poverty levels because development is not just a process in which the poor become rich but also a process in which the rich get richer (Laporan Kualiti Hidup Malaysia, 2011). Therefore, the Malaysian government acknowledges that educational transformation plays a pivotal role in its economic growth and the overall development of the country.

Based on this, the Malaysian government outlines its 2013–2025 Education Development Plan (Pelan Pembangunan Pendidikan, 2012), which is focused on numerous measures that will be implemented in order to ensure that the educational system is transformed. Among these measures is the use of language in the teaching and learning process. This is based on the understanding that language planning and policy can yield necessary assistance for transforming the country and its society in a radical way because language planning is pivotal when it comes to changes in revolutionaries. In line with ideology, considering that there are numerous ethnic groups in Malaysia, Malay is considered the general language for all, while the Chinese, Indians, and other ethnic minorities are to retain their own mother-tongue as well as ensure that they are actively being used (Tan, 2005). In any case, the English language is widely adopted in both social and professional contexts. This ensures that the Malaysian workforce is skilled in more than one language. Thus, it is the Malaysian identified that requires illumination – pointing to the fact that Malaysia is a multi-lingual nation with people being fluent in their mother-tongue (the Malay) and English language. In any case, it is important to point out that there are variations in the competence levels for these two languages. This led the government to initiate the new education policy known widely by its Malay acronym MBMMBI (Memartabatkan Bahasa Malaysia dan Memperkukuh Bahasa Inggeris), with its English translation being "To Uphold Bahasa Malaysia and to Strengthen the English Language." This is an effort that needs to be heightened.

In so doing, it is vital to shed light on what bilingual education pertains to. In accordance with Krashen (1999), it is vital to distinguish between the two goals of bilingual education, which are: the development of academic English and school success; and the development of a heritage language. Both goals are attained through quality bilingual education programs, which are made possible through proper calculation and implementation of necessary supporting policies. The main objective of the bilingual policy is to ensure that learners are able to master two languages: Malay and their ethnic mother-tongue. However, a lot of importance is accorded to English because the mastery of English helps people access a vast level of information in today’s globalized world (Ministry of Education, 2008). Without much doubt, it is clear that globalization has brought about an unprecedented penetration of the English language (Zuraidah et al., 2011). Based on that, it is clear that students who learn the English language will experience numerous benefits. Therefore, a bilingual policy, as is the case in Malaysia, is the best approach to ensure that the Malaysian populace benefits from both modernization and globalization.

The Common European Framework of Reference for languages

The Common European Framework of Reference for languages (CEFR) was developed by a Council of Europe’s international working party that was established by the language policy division with the aim of promoting coherence and transparency in the teaching and learning of modern languages in Europe (Simon and Inge, 2013). Following a pilot scheme that involved an extensive consultation on the field, the framework became official in 2001 when it was published, and it is known as the European year of language, and it has since been translated into 40 languages both in Europe and other parts of the world (Simon and Inge, 2013).

The CEFR features a descriptive scheme of language use and competencies together with associated scales of proficiency for the various parameters in the scheme. It also features chapters on the design of curriculum, the methodological options for learning and teaching languages, and the principles that should be employed when assessing or testing languages. There is also a comprehensive descriptive scheme that is focused on the learners, which provides the readers with the necessary tool for reflecting on what is required for language use, learning, teaching, and assessment (Simon and Inge, 2013). Thus, the CEFR provides a common ground and a common language for understanding language curriculum, syllabuses, guidelines, teacher-training programs, textbooks, and other related examination and qualification standards. It provides the different partners involved in language planning, delivery of language provisions, and assessing language progress and proficiency with the opportunity to coordinate and situate their varied efforts.

In the CEFR, the descriptive section is based on an action-oriented approach to learning and using language. It offers an analytic guide of what is required of proficient language users in order to ensure that they attain effective communication as well as the numerous forms of skills and knowledge that they need to acquire.

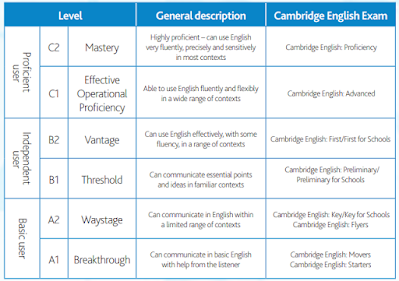

Figure 1: Summary of the CEFR Levels

Source: Simon and Inge (2013)

There are six proficiency levels described by the CEFR for learning a foreign language. The second levels are BI and B2, which are known as "independent users," and the final levels are C1 and C2, which are commanded by "proficient users." The definition of these levels is based on the definitive action-oriented approach employed by the CEFR creators. In this approach, users and learners of foreign languages are viewed as members of a society who complete tasks under specific conditions and within a predetermined social context. As such, the levels as described in the scale are defined by a "can do" statement that describes what the learner should be able to effectively communicate or do in order to be considered successful at a given CEFR level. Aside from the general description accorded to each of the CEFR levels, the "can do" statements are used to describe the varied skills such as: reading, listening, speaking and interaction, spoken production, and writing.

The challenges of implementing CEFR in education systems

Previously, discussions have been centered on the six levels of CEFR and the expected outcome from implementation. However, this doesn’t mean that there are no associated challenges and difficulties when it comes to ensuring successful implementation. While the challenges and difficulties associated with the implementation of CEFR do depend on the extent to which it is implemented in the education systems, two major issues are frequently featured as:

There is no empirical evidence that successful implementation of CEFR levels and learning outcomes, curricula objectives, assessment, and other documents would have a positive impact on education systems; and

The extent to which CEFR is being adopted by modern language teachers in their language lessons (Simon and Inge, 2013).

For example, both the Swedish and Hungarian education systems noted that poor implementation was due to a lack of empirical proof because no research study was conducted to investigate the relationship between CEFR implementation and overall language outcomes in the countries (Simon and Inge, 2013). Even in the Netherlands, there are numerous research studies, ‘linking research', which is known as' koppelingsonderzoeken’ in Dutch, conducted to establish the relationship between examination programmes and the CEFR on the one hand, and the CEFR and assessment of examinations on the other hand. However, up to date, none of these studies have been able to show that there is any learning outcome determined by the implementation of CEFR levels (Simon and Inge, 2013). The reasons are that: 1) there is no clear distinction established between the CEFR levels; and 2) the levels of description used for the CEFR are too wide and, as such, do come with multiple interpretations.

Additionally, when it comes to implementing the CEFR within the teaching process of a modern foreign language, it is mandated that a different approach to teaching be employed and this limits overall implementation levels (Simon and Inge, 2013). That is to say, teachers will need to acquire skills for executing their teaching process in an action-oriented approach consistently and they will need to learn how to evaluate the learning outcomes recorded by the pupils in a way that is aligned with the CEFR terms. In practice, the implication is that the teachers will need to focus less on the language grammar and focus more on training the people on how to actually utilize the language in practice (Simon and Inge, 2013).

The MBMMBI policy and major challenge of implementing the CEFR in Malaysia

Basically, the MBMMBI policy is geared toward students at both schools and higher education providers (HEP). At the HEPs, it is particularly of vital concern considering that it is related to how Malaysian graduates are marketable or employable, with numerous studies highlighting poor English and Malay communication (especially during first interview) as one of the main sources of employability among Malaysian graduates (Nik et al., 2012).

In the Malaysian Education Plan (Pelan Pembangunan Pendidikan Malaysia, 2012), there is also a clear indication of the need for the Malay language and the English language curriculum and assessment to be aligned with the provisions made by the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR), which entails adopting the CEFR as the benchmark for all language plans and policies in the country. In accordance with the plan, the expectation is that all students in Malaysia should be able to attain the "operational proficiency" levels that have been defined by the CEFR as the measure of linguistic fluency and as such is mandated for them to fully participate in both academic and professional life. This is because bilingual proficiency is one of the major attributes required for people to be globally competitive (Pelan Pembangunan Pendidikan Malaysia, 2012). In the CEFR, there are common grounds for discussing and understanding language syllabuses, guidelines for the curriculum, assessments, textbooks, and so on across the various education systems where they are employed. It provides a comprehensive description of the knowledge and skills that are necessary for developing the ability of students to effectively act. In this description, the cultural context for setting the language is also covered. There are also proficiency levels provided in the framework, which makes it possible for learners to progress through measured stages of learning and keep progressing on a life-long basis (Council of Europe, 2001, p. 1). Presently, the CEFR is now an internationally accepted standard for teaching and learning languages (North et al., 2010), and its influence is cutting through Europe and other parts of the world. In any case, it should be noted that earlier discussions pointed out that the CEFR is a language-independent framework, which is based on an action-oriented approach.

From an analysis of the CEFR, it has been found that the objective of the CEFR does entail guiding practitioners on how to develop objectives and choose the right strategies and approaches in line with the particular context offered by the CEFR (North, 2004). In this study, it was discovered that the CEFR is a flexible tool used for facilitating communication, reflection, and networking. That is to say, it can be utilized to ensure a greater number of contexts used is possible in line with the particular need defined by the context, and at the same point, it allows for the context to adhere to the major principles of the common framework. Presently, the CEFR standards are being employed across Europe by different stakeholders for different educational levels (Figueras, 2012). In its general sense, the CEFR was originally developed for foreign language learning but is now being widely used for L1. In accordance with Martyniuk and Noijons (2007), these standards are also being employed for teaching languages for specific purposes.

On a similar note, CEFR is widely employed in the Malaysian Ministry of Education as a framework in line with the policies of the MBMMBI (Malaysia Education Plan, 2012–2025). In any case, it is vital to point out that the CEFR only offers guidelines for interpreting the language ability of students. In the Malaysia standards, there is a need for a clear framework to be established that will be used for educating and assessing bilingual education, which will cover both the Malay and English language, providing guidelines for the teaching and learning process as well as HEPs and the assessment of students’ performance (Hamidah et al., 2014). Such a framework can be used as a guideline for planning and implementing bilingual activities that are geared towards enhancing the value of Malaysian graduates. Thus, it is also required that the educational system develop a framework for bilingual education and assessment, and the lack of such is the main challenge being faced for the implementation of CEFR in the Malaysian context (Hamidah et al., 2014).

References

Cooper, R. L. (1989). Language Planning and Social Change. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511620812 [Accessed 10 June 2018].

The Council of Europe (2001). European framework of reference for languages. Language Policy Unit, Strasbourg. Available at: http://www.coe.int/lang-CEFR [Accessed 10 June 2018].

N. Figueras (2012). The Impact of the CEFR 477–485. ELT Journal, 66(4).

Hamidah, Y., Nur-Farita, M., U., & Muhammad, I., M. (2014). Upholding the Malay Language and Strengthening the English Language Policy: An Education Reform. International Education Studies; Canadian Center of Science and Education, Vol. 7, No. 13, pp: 1913-9039.

Kaplan, R. B., & Baldauf, R. B. (2008). An Encyclopedia of Language and Education Hornberger, N. H. An Ecology Perspective on Language Planning Springer US https://www.springerlink.com/content/g0j2181601014436/ [Accessed on the 10th of June, 2018]. .

Krashen, S. D. (1999). Condemned Without A Trial: Bogus Arguments Against Bilingual Education NH: Heinemann.

Malaysian Quality of Life (2011). Unit Perancangan Ekonomi, Putrajaya: Jabatan Perdana Menteri, learning, teaching, and assessment. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Martyniuk, W., & Noijons, J. (2007). Executive Summary of Results of a Survey on the Use of the CEFR at National Level in the Council of Europe Member States http://www.coe.int/t/dg4/linguistic/source/survey_CEFR_2007_EN.doc [Accessed on the 10th of June, 2018]. .

Education Ministry (2008). The Development of Education Ministry of Education, 2008. http://www.unesco.org/IBE/National_Reports/ICE_2008/Brunei_NR08.pdf [Accessed on the 10th of June, 2018]. .

Napisah, K. (2017). Examining a policy strategy for high-quality Malaysian English Language Teachers. Malaysian Journal of Learning and Instruction, 14(1):187–209. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1150438.pdf [Accessed on the 10th of June, 2018]. .

Nik, H. O., Azmi, A. M., Rusyda, H. M., Arena, C. K., & Khairani, A. A. (2012). Employability skills of graduates based on current job demand via electronic advertisement Asian Social Science Journal, 8 (9).

North, B. (2004). Europe’s framework promotes language discussion, not directives. Guardian Weekly, Thursday, 15 April. http://www.guardian.co.uk/education/2004/april/15/ [Accessed on the 10th of June, 2018]. .

Malaysian Education Development Plan 2013-2025 (2012). Putrajaya: Kementerian Pendidikan Malaysia.

Robinson, D. (1998). Language Policy and Planning ERIC Digest Available at: http://www.ericdigests.org/pre-9210/planning.htm. [Accessed on the 10th of June, 2018]. .

Simon, B., and Inge, V. (2013). The implementation of the common European framework for language in European education systems. A publication for the European Parliament. www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/etudes/join/2013/495871/IPOL-CULT_ET(2013)495871_EN.pdf [Accessed on the 10th of June, 2018]. .

Tan, K. W. (2005). The medium-of-instruction debate in Malaysia English as a Malaysian language? Language Problems and Language Planning Available at: http://www.factworld.info/malaysia/news/debate.pdf [Accessed on the 10th of June, 2018]. .

Zuraidah, Z., Farida, I. R., Haijon, G., Chuah, B. L., & Katsuhiro, U. (2011). Internationalization of Higher Education: A Case Study of Policy Adjustment Strategy in Malaysia International Journal for Cross-Disciplinary Subjects in Education (IJCDSE), Special Issue, 1(1).