Behavioral factors influencing investors’ decision making in stock exchange

CHAPTER ONE

INTRODUCTION

1.1. Research Background

For a long time, researchers have been very interested in the human decision-making process.In the early works done on this topic, the studies approached it from an economic perspective (e.g., Schiffman & Kanuk, 2007; Fama, 1970). There are some theories that have been used to this effect, and one of the more prevalent ones is the utility theory, which proposes that individuals make their choices by taking the expected outcome of their decisions into consideration. As such, a rational decision-maker is one who avails himself or herself of the necessary information needed for analyzing the available options and adopts the course of action that would bring about the best result (Schiffman & Kanuk, 2007). In the past, portfolio theory has pushed support for the rational decision-making of an individual (Markowitz, 1952), capital asset pricing (Sharpe, 1964), and the efficiency of the capital market (Fama, 1970). In any case, it is important to point out that these theories no longer have the privilege of providing the motivation, adequate information, or time necessary for the decision makers to make a perfectly rational decision (Simon, 1997). In behavioral economics, it has been shown that humans don’t make decisions naturally like a rational being is expected to do. On the contrary, it has been widely accepted that humans make mistakes regularly in their decision-making (Tomer, 2016). Individuals, as human beings, are normally described based on the notion that they often seek satisfaction instead of making optimal choices (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974). Therefore, the question that normally emanates from these descriptions is whether the concept of irrationality is something that is in line with those making decisions because they are supposed to be rational in the course of making decisions. In this study, an attempt is made to explore this phenomenon, which serves as the overall objective of the study because it assesses the behavioral factors that influence an individual's intention to invest in the stock market.

Since it is already agreed from the above discussions that decision-making can be rational or irrational, understanding the factors that influence the path through which one decides is crucial. In the case of investors, irrational decision-making could be the result of psychological or cognitive biases. In line with the work of Bernstein (1998), evidence exists to show that there are repeated patterns of inconsistency, irrationality, and incompetence in the way that humans arrive at their choices and decisions because of the different kinds of uncertainties they are faced with in the process. Probably, the presence of this phenomenon in the financial market is the reason for the failure of risk management systems because they are normally based on the neoclassical assumption that distributions are normal (Chittedi, 2014). In terms of literature, research in financial marketing is heading towards the behavioral aspects of the investor instead of sticking to the conventional or fundamental approaches (Listyarti & Suryani, 2014; Olokoyo et al., 2014; Sandberg et al., 2016). This comes with an alternative view that looks at the behavior of humans; thus, the paradigm of behavioral finance is shifting to focus on other theories that can broaden the understanding of multidisciplinary human behavior (Tuyon & Ahmad, 2016). Such a transition in financial research as has been experienced in recent years doesn’t function to unwind the measures that could be used to validate the basis of behavioral finance.

The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) is an extension of the early work done by Ajzen and Fishbein (1980), the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA). TPB has transformed into one of the dominant theories that is being applied in different areas of behavioral study (Shaw & Shiu, 2013). The assertion held in this theory is that attitude towards behavior, subjective norms, and behavioral control all come together to collectively form behavioral intention (Ajzen, 1985). In terms of attitude toward behavior, it simply means the extent to which an individual has a favorable or unfavorable evaluation of the behavior that interests him or her. Subjective norm, on the other hand, is defined as the perceived social pressure that forces a person to perform or refrain from performing a behavior.Finally, perceived behavioral control is considered to be the perception that one has about ease or difficulty in conducting the behavior that emanates from the existence or absence of the resources and opportunities required.

In the course of the past two decades, a number of studies have been conducted that have validated TPB and discovered that it is useful when it comes to understanding and predicting the behavior of people in different fields of life (Husin & Alrazi, 2017; Warsame & Ireri, 2016; Kovac et al., 2016). In the context of financial literature, the theory was adopted by Gopi and Ramayah (2007) to predict the intention of Malaysian investors to trade online, and the researchers established a relationship between the attitude towards behavior, social norms, and perceived behavioral control. In a more recent study, Adam and Shauki (2014) illustrated that there is a positive correlation between attitude, subjective norms, moral norms, and the intention of socially responsible investors in Malaysia to behave in a certain way. Similar studies have been conducted in Singapore, where Lee-Partridge and Ho (2003) assessed the adoption of online stock trading among investors. Their research showed that attitude and social factors are crucial when it comes to predicting the behavioral intentions of investors. Based on the findings from their survey, it was discovered by Mahastanti and Hariady (2014) that the intention of female lecturers in an Indonesian university to buy financial products was influenced by their risk preference and perceived behavioral control. In any case, it should be pointed out that this study didn’t offer substantial evidence that can be used to create the correlation between subjective norms, attitude, and behavioral intention. In summary, the studies that have been conducted in the past in relation to financial behavior have adapted the TPB in the course of predicting the behavior of investors toward purchasing financial intentions, but the studies conducted in reference to Malaysia have been limited. While there are a significant number of literature reviews that have been conducted where the application of TPB has been illustrated in different contexts, there is still uncertainty as to whether this model should be adopted in its basic form or if any expansions should be made prior to the adoption. In view of these issues, this research is designed to assess the behavioral factors that influence the decision-making process of investors with respect to the Malaysian stock market.

1.2. Research problem

While scholars have pointed out that behavioral finance is of high importance (Tuyon & Ahmad, 2016; Chittedi, 2014), the focus of the Malaysian study has been limited. In their observation, Kumar and Goyal (2016) pointed out that investors followed a rational decision-making process when investing, but the individual might have behavioral biases that can arise at different stages of their decision-making. Their findings indicate that this has influenced the different results obtained between genders. On the same note, other studies exist (Prabhu & Vachalekar, 2014; Kumar & Rajkumar, 2014; Subramanya & Murthy, 2013) that have focused on the Asian market, with their findings indicating that the investment behavior of investors in the Asian market is significantly influenced by behavioral factors. However, the focus of these studies has been on the investors’ demographic profiles. In the case of Malaysia, the study of behavioral factors that can influence investment decisions in the financial market is a fairly new area of study. Continuing on this, the study of determinants in aspects like the socio-psychological features of investors is an area that has not gotten significant attention. As such, it is imperative that the necessary research be conducted in this area in order to establish the validity of the individual behavioral factors that influence the decision-making of investors in the stock market. This is even more significant in Malaysia because much has not been done in the context of Malaysia.

As noted by Kidwell and Jewell (2008), the past behavior of investors plays a pivotal role in determining their present behavior. Notwithstanding this, there is little information about the impact that past behaviors can have on the information processing of individuals within the model (Wood et al., 2005). For example, whether an individual with limited experience will be motivated to consider cognitive resources, such as evaluating their silent beliefs in the course of making decisions, or whether an individual with higher or more extensive experience will be likely to ignore the available information and instead rely on their past successful behavior in order to overcome their perceived level of difficulty before making decisions.When one relies on past actions or behaviors, it is considered a cognitive bias. Normally, people seem to ignore important information and act in ways that are termed irrational, which is in line with the theories of behavioral finance. It has been noted that these cognitive biases manifest in three major ways: representation, anchoring, and availability. Considering that they represent the past experience or behavior of an individual (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974), they seem to be crucial in determining how the individual makes their present decisions. As such, the past behavior of investors (in relation to their past investing experience) is also taken into account when making use of the TPB model in order to ensure that the impact of behavioral factors on the investor’s investment decisions is better understood.

Aiming to address these needs, the present study is thus designed to provide insight on the behavioral factors that influence the decision-making process of individual investors in the Malaysian capital market. This is based on the expansion of the literature on behavioral finance by adopting the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), which has been widely adopted in other studies. This study adopts the three elements of the theory as follows: the attitude of the investors towards their investment portfolio, subjective norms, and the perceived level of control that the investor has. As such, this research doesn’t go beyond the definitions made in this theory and isn’t an expansion of the existing theory. The research will also adopt the value-belief-norm (VBN) theory. Although the VBN theory has been widely used in the area of environmental behavior, this research aims to assess its potential influence when it comes to investment behavior.

1.3. Research objectives and questions

Based on the discussions above, the objective of this research is to: present a comprehensive assessment of the behavioral factors that influence investors’ decision-making processes on stock exchanges. In order to attain this objective, this research will ask a number of questions, including:

- What exactly is the decision-making process?

- What are the common behavioral factors and how do they influence decision-making?

- What are the behavioral factors that influence the decision-making process of investors on the stock exchanges?

It is through the answers to these questions that the research can be considered successful.

1.4. Research scope

As pointed out earlier, this research will focus on the theory of planned behavior in relation to the behavioral factors that influence the purchase decisions of investors in stock exchanges. Therefore, three variables—attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control—will serve as the focus of this research.

When it comes to attitude, it is defined as the cognitive and psychological behavior that an individual exhibits based on their assessment of any given element with some level of favoritism or non-favoritism (Eagly & Chaiken, 1993). For the individual in question, it helps in deciding whether a given action should be undertaken or not based on the consideration of the positive and negative consequences that such an action would yield. In this regard, the behavioral intention of an individual will be influenced by the assessment of the positive or negative outcome of the said behavior. When the individual's attitude is more positive, the behavioral inclination is stronger. On the same note, when the attitude is more negative, the behavioral inclination gets weaker.

Findings from existing research (Wood & Zaichkowsky, 2004; Fünfgeld & Wang, 2009) have demonstrated that the attitude of investors towards risk does influence their investment behavior. In these studies, it is stated that people have different levels of risk tolerance, and as such, they treat risks differently (Wood & Zaichkowsky, 2004; Fünfgeld & Wang, 2009). The impact of this is that it alters the behavioral intentions of investors.When investors are risk-averse, they are more likely to put their money in bank accounts, which yield a low but guaranteed interest rate, rather than stocks, which yield high values but also carry the risk of losing the money entirely.

In other studies, such as those undertaken by Kaiser et al. (2007) and Dickson (2000), the observation is that the behavior of investors can better be predicted when their attitude towards a given financial product is established. For these researchers, attitude is a factor that can have an influence on the intention of an investor to go for wealth management services. As evidenced in past studies (Mandell & Klien, 2007; Borden et al., 2008), there is a positive correlation between attitude and the behavioral intention of individuals in the context of financial decision-making. More of the focus on attitude in this case will be viewed from the context of financial decision-making in relation to the decision of an investor to choose one security over another.

Subjective norms are an individual's perception of how they will be perceived by those they use as reference groups if they engage in a particular behavior (Cialdini & Trost, 1998).It can also be defined as the "perceived social pressure" that one goes through, which forces them to perform or not perform a given behavior in a given circumstance (Ajzen, 1991). Just like in the case of attitude, there are extensive studies on the influence of subjective norms on decision-making, and it is considered to be the outcome of the normative expectations that one has from close family members, friends, and relatives (Cavazos, 2013). Across different studies (e.g., Sharma & Gupta, 2011; Croy et al., 2012; Koropp et al., 2014), an assessment of the influence of subjective norms within the context of financial investment has been undertaken. Based on the findings from these studies, subjective norms do have considerable influence on the decision-making of investors, and in cases where the investor has less financial knowledge, the person will heavily rely on the views of their relatives, family members, and close friends when making investment decisions.

Based on the views of Hong et al. (2004), elements like relationships with neighbors and church visits can actually play the role of proxies in sociability. These elements help foster the participation of individuals in the stock market. As such, social norms are considered to be the change in thinking that is reflected in the behavior of an individual as a result of the relationships that the person has with others. The implication here is that while an individual might not have a constructive attitude towards an investment, their individual behavioral intention can also be influenced by the incongruence between the person’s attitude and the expectations of close others. Therefore, these respective individuals might end up pursuing investments in the stock market in order to ensure legitimacy because they might be seeking to create a balance between the perception of other people and their actions. This is the second scope of this research, and it will look to offer a clearer view of the influence of subjective norms on the behavioral intentions of investors in the stock exchanges.

Perceived behavioral control refers to an individual's perception of the ease or difficulty with which they can carry out their desired behavior (Ajzen, 1991).In the case of this study, it refers to the perception of an individual investor about the ease or difficulty with which they can invest in a given security market or set of securities. Based on past studies (e.g., Lin, 2010; Gopi & Ramayah, 2007; Blanchard et al., 2008), which were conducted in different contexts, there is enough evidence to show that perceived behavioral control has a significant influence on behavioral intention. When it comes to financial decision-making, it is suggested by Mahastanti and Hariady (2014) that perceived behavioral control can actually be the sole predictor of the intention of investors to invest in a given stock. The finding from this research is that when an individual has the ability and opportunity to invest in the stock market, the person will be motivated to undertake such actions. Another study was conducted in these areas by Phan and Zhou (2014), which shows that the element of behavioral control can be used to explain why Vietnamese investors behave in a certain way in the Vietnamese stock market. These researchers further highlighted in their study that information acquired from friends, family, and relatives, past experience in investment, and the availability of necessary resources all help the investor to define their perception of ease or difficulty in the course of determining their investment choice. Based on the preceding arguments, this study proposes that investors perceive behavioral control as having an impact on their investment decision-making process.This is the final scope, and this research will focus on the influence of perceived behavior control on behavioral intention within the context of stock exchanges.

1.5. Significance of the Study

Considering the overall purpose of this study and the impact that findings from the study are expected to have, it is concluded that this study is significant for a number of reasons.

The first point to mention is the practical contribution.For business policymakers, this study is important because it will shed light on the behavioral factors that influence the purchase intentions of investors in stock exchanges. This is important because the goal of any company that is listed on a securities exchange is to generate more investments that will be used in the pursuit of their overall corporate objectives. Therefore, through the understanding that will be developed in this research, those responsible for enacting policies geared towards attracting more investment will be able to understand the investors better and create policies that can bring about positive behavioral intentions from the investors towards their security. This is even more significant in the case of Malaysia, where it has been illustrated that limited studies have been conducted in Malaysia based on the context of this present study.

The second is the theoretical contribution. This research is also important for scholars and readers. This is because the findings from past studies in relation to the three behavioral factors in this case have been mixed. Some have shown that there is a positive correlation; others show a negative correlation, while it has been shown in other research that there is no correlation. Thus, this present study will help to validate the existing findings in terms of whether there is a relationship or not and the extent of the relationship. On the same note, it will also serve as the basis for further related studies within the context of study in general and the Malaysian sphere in particular.

1.6. Research outline

This research will be divided into five chapters. The first chapter is the introduction, and it will give a background overview of the research together with the overall objective and the outline that will be adopted in this study. This will be followed by a review of literature in the second chapter. In this chapter, the research will ensure that past related studies are reviewed and the reader has better insight on the variables being adopted by defining them and showing how they will be applied. This chapter will also contain the conceptual framework of the study. The third chapter is on the research methodology, detailing approaches and measures used to gather data for the primary research. This will be followed by an analysis of the gathered data in the fourth chapter, while a conclusive summary of the findings from the study will be presented in the fifth chapter.

CHAPTER TWO

LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1. Introduction

In the literature, it is considered that the key element when it comes to decision-making in the financial market is the information processing of the investors, and the reason is that it features the key factors of the final decision they make with respect to any given stock (Mahmood et al., 2011). The emphasis laid by behavioral finance is that opening this "black box" will make it possible for one to explain the inefficiencies being observed in the financial market, but the fact is that they cannot be predicted by the Efficient Markets Hypothesis (EMH). The essence of this knowledge is that it makes it possible for the decision-makers to define the behavior of strategies that will be used to reduce the gap between efficient markets and actual markets. Thus, the study of the decision-making process is considered necessary not just when it comes to explaining the dynamic nature of the financial markets but also due to its ability to aid financial advisors in developing the right view of the activities associated with advising in a way that is more effective (Kahneman and Riepe, 1998).

This study serves as an extension of the past studies that have been done in the investment decision-making process towards developing an investor cognitive model with three stages in order to assess the factors that drive the investor’s decisions and provide fundamental evidence on the relationship between the individual traits and environmental factors in the course of making such decisions. To the very best of the researcher’s knowledge, the interaction of the particular variables considered in this case has been studied previously but not as extensively as this present research aims to address it. They include attitude toward an investment portfolio, subjective norms, and a perceived level of control. However, all of these variables are influenced by the cognitive level of the investor.

In essence, the financial decision-making process is constrained and compelled by non-financial factors. They include context factors like characteristics of the individual’s personality, and they moderate the way in which the decisions are affected by the environment (Holden, 2010). When it comes to the environmental factors that yield influence on the decisions of investors, one that plays a crucial role is their level of information asymmetry. Investors decide on the stock to purchase based on an assessment of the investment's uncertainties as determined by the information they have gathered from different sources (Mahmood et al., 2011). In an argument by De Bondt and Thaler (1994), which was made in their pathbreaking paper, it is indispensable for one to consider psychological processes and variables when assessing the market. Based on the same view, Statman (1999) denied the notion that psychology was introduced into finance by behavioral finance, based on the notion that psychology was never out of finance. On a final note, it was stated by Oberlechner and Hocking (2004) that empirical research that is psychologically informed can bring about a better understanding of information processing in the market because it considers the attitudes of the participants as well as the role that information sources have on the decision-making process of the investors.

Previous research has shown that there is an arousal of different information processing among different investors.This evidence does reveal that it is difficult to identify the individual characteristics that influence the decision-making process. Maybe this is the reason why in literature, the individual characteristics of investors are normally represented based on demographic features such as sex, age, experience, and qualifications. Notwithstanding this, the influences that demographic variables have on the decision-making of investors are normally explained through the application of their different attitudes and cognitive abilities. On that note, it is considered appropriate that the model of cognition be introduced into this instead of the individual demographic variables in order to better assess the influence of these factors on the purchase decision of the investors (Santos et al., 2011).

There are three stages in this cognitive model: noticing, sensemaking, and action. In this model, what is taken into account is that processes like action and perception are normally included in cognitive models (Lovric et al., 2008), and this also integrates the argument that has been made by Starbuck and Milliken (1988) in relation to classifying perception into sensemaking and noticing. In this case, identifications are made in relation to how investors notice some news about stocks while ignoring others, interpret this news in a certain way, and finally make the decision to buy the said stock.

After the discussions on the cognitive model, this section of the paper also introduces the theoretical framework that will form the basis of this present study. The theory used in this case is the theory of planned behavior, which features attitude, subjective norms, and perceived level of control (individual traits) as having influence on the purchase decision-making of the investors.

2.2. Discussion of the investors’ cognitive model

In an argument presented by Garca-Ayuso and Jiménez (1996), research in the field of financial decision-making can be undertaken based on cognitive models. It was also illustrated by Lovric et al. (2008) that processes like action and perception are normally included in cognitive models (e.g., Sloman, 2001; Warren, 2006).

Perception is considered the cognitive process through which individuals gather information and create an image of the reality they have about their surrounding environment based on the information they have gathered. However, such perceptions yield an awareness of reality that is not perfect. As such, based on the same information stimulus, it is possible for one individual to see that the perceived realities of two individuals are different (Fahey and Narayanan, 1989). In this literature, the emphasis is on the diversity of the factors that affect and intervene in the process of perception. Besides, the process of perception entails going through different phases. Particularly, the process of perception can be grouped into two stages: the first stage is "noticing," where signals (relevant information) are distinguished by the individual from the noise (irrelevant information), while the second stage, "sensemaking," is where the individual interprets those stimuli that were previously considered signals (Starbuck and Milliken, 1988).

Martinez and Gonzalez (2018) developed a more integrated proposal in order to define a cognitive model of investors’ decision-making based on three stages: noticing, sensemaking, and action. As discovered by Oberlechner and Hocking (2004), the financial markets might be less about the actuality of economic facts than they are about the information that has been noticed and how it is interpreted by market participants, emphasizing the importance of the attitude of the market participants when it comes to the information process.

In the decision model, sensemaking is a pivotal element because, in line with the argument by Starbuck (1988), when people are unable to notice the vital changes, they will find it difficult to comply with their goals. Such difficulties normally emanate either as a result of the individuals not changing the way they utilize their knowledge properly or because they have not realized the need for them to make further advancements on their knowledge. Investors’ intentions were studied by Karlsson et al. (2005), which focused on the capacity of the investors to address or ignore information. In other words, the authors assess the capacity of the investors to consider stimuli as either noises or signals. The next stage involves making sense of the noticed signals after the investor has noticed the stimuli and differentiated between signals and noises.Based on what is obtainable in the case of noticing, all investors don’t interpret the relevant information in the same way (Starbuck and Milliken, 1988; Braunstein and Welch, 2002; Santos and Barros, 2011) as a result of individual traits.

On a final note, action is said to manifest when the investors change their present portfolio (Lovric et al., 2008). Based on the views presented by the past authors, the phase of action includes decisions on the asset to choose, the volume of asset to trade, the form of order that needs to be sent to the market, and the rest of the parameters that are required for completing the order.

2.3. Behavioral decision-making

Unlike what is obtainable in the conventional theories of finance, it is suggested by modern theories that investors’ decision-making is not brought about by considerations and is normally inconsistent. In other words, when making investment decisions, investors are not completely rational. This is based on the notion that their decision-making processes are normally influenced by different psychological and cognitive errors. Investors must then work towards making sure that they have a clear picture of the emotional and cognitive errors that might influence their decision-making process. It was termed "bounded rationality" by Herbert Simon (Tversky, 1990). In accordance with the discovery made by Tversky: i) people normally demonstrate risk-seeking behavior in the course of making investment decisions, and this is in contrast with the assumption of risk-averse investors; ii) the outcomes of various decisions are normally attributed differently by investors; and iii) their expectations, which are considered to be rational under classical decision-making, are normally biased in predictable directions.

From the past literature in relation to behavioral decision-making and the psychology of the individual investor, which is available across different channels, one can have a fair understanding of the emotional and cognitive biases to which the individual decisions of investors might be susceptible. In this section, the researcher aims to discuss these biases by relating them to the decision-making process. They are as presented below.

This is based on the notion that individuals have the tendency to make hasty decisions, and it simplifies the strategies employed for addressing complex issues and limiting explanatory information. Normally, individual investors make their decisions based on the trial-and-error method, which led to the development of the "rules of thumb." To simplify this, investors make use of rules of thumb for processing complex information in order to arrive at their investment decisions. It is possible that the investor obtained the correct information and evaluated it objectively before entering such a realm, but it is extremely difficult to separate one's emotional error from their cognitive error during the decision-making process.At some point, it might bring about favorable decisions, but in most cases, it brings about poor and unfavorable decision outcomes (Chandra, 2017). The heuristics list includes:

- Representativeness heuristics, which are based on the notion that investors seem to assess the chances of an event occurring in the stock market by attending to its similarity to other events, This kind of assessment is biased, and the implication is that it might result in an overreaction on the part of the investor. For instance, if an investor discovers that a leading fund, brokerage firm, or elite personality has invested in a certain stock, they might end up buying the same stock without having a clear objective for that purpose. On a similar note, if impressive results are reported by the industry leader, other players in the industry will also benefit because investors will not seem to consider the industry as profitable, even when such might not be the case in the long run. Such heuristics do lead to investors blindly following others' portfolios (Chandra, 2017).

- Overconfidence: while to some extent, confidence is considered pivotal for success, it doesn’t always function in the interest of the investors. When it comes to the stock market, the confidence of the investors normally leads to excessive trading. According to Odean (1998), high volume trading is the result of investor overconfidence.Overconfidence can be considered the tendency of the investor to consider himself or herself skilled. They tend to forget the concept that "a rising tide is responsible for lifting all boats" in moments when their investment decisions seem to be good. They seem to overestimate their own potential. According to Glaser and Weber (2003), overconfidence has three components: miscalibration, the "better-than-average" effect (in which people believe they have higher-than-average skills), and the illusion of control (in which one believes his or her personal probability of success is greater than the objective probability that would warrant such).It is established that besides miscalibration, all other aspects of overconfidence bring about higher trading activities (Chandra, 2017).

- Availability heuristics: heuristics that are based on availability are the ones that indicate that the investors are inclined to offer a higher probability to events that they have familiarized themselves with. It is more evident in the case of the recall. This is based on the notion that people are more likely to base their judgments on events that are recent or easy to remember instead of occurrences that are similar but harder to recall. In the bullish stock market, the news is only positive, but only negative ones are recorded in the bear market. A recent example is the case of the Sensex in 2008, which rose above 20,000 and everything appeared to be fine; however, in October of the same year, there was an unprecedented financial crisis, and the Sensex plummeted.Therefore, it can be concluded that the upward or downward movements experienced in the stock market are based on reflexes (Chandra, 2017).

Rogue is the frustration that one experiences due to bad decisions. In the context of investment, "regret" refers to the emotional reaction that an investor is having in relation to a mistake that has been made. Based on the earlier discussion, the joy that emanates as a result of gratification and the pain are all considered pivotal when it comes to understanding the influence that behaviors have on investment decisions (Chandra, 2017). As a result, the aversion to regret and desire for gratification cause losses to be delayed and profits to be realized.For some investors, this situation particularly holds true. This is because when such investors are faced with the fact that they have made the wrong decisions, they seem to avoid selling the stock following its decline in value, resulting in prompt sales on the stocks that have increased in value. By so doing, it is expected that the investors shouldn’t admit their mistakes or feel regret or take necessary measures that will make them avoid the feeling of regret while still hanging on to a share with the prices declining.

This is used to refer to the psychological conflict that emanates from simultaneously held attitudes and incongruous beliefs. Leon Festinger (1989), a psychologist, introduced this concept in the late 1950s. When confronted with the challenges of new information, the author and other researchers demonstrated that the majority of people seek new ways to preserve their current understanding of the world by rejecting, discarding, or avoiding the use of these new information or convincing themselves that there is no real conflict between past and present information.Thus, cognitive dissonance is viewed as the reason why people change their attitudes. That is to say, it is the mental conflict that the investors experience following their realization of the mistake they have made.

In the context of investment decisions, cognitive dissonance is defined as the pain of regret caused by incorrect beliefs.Normally, individual investors don’t want to change their decisions; they end up convincing themselves that their decisions are rational. Kumar and Chandra (2007) conducted a study that assessed the sentiments of investors and discovered that the majority of them want to sell the group of stocks that produce the best profits and have to convince themselves that their decision to withhold the selling of those stocks that are yielding losses is the right one based on the notion that they will eventually increase in value later. It is common to see this approach in the individual behavior of investors in the financial markets (Chandra, 2017).

Normally, investors don’t conduct adequate research about the stock they want to invest in because there are simply too many data points that need to be collected and analyzed. Instead, they anchor their decisions based on simple figures or facts that might end up having little or no influence on their decisions, ignoring information that is crucial like the earnings expectations for a stock, as the investors seem to anchor most of their decisions on recent information (Hoguet, 2005). As a result of this, investors seem to underreact to new information. For instance, a financial analyst might anchor their decisions on forecasts and normally underreact to new information when they are making revisions. For the investors, the point of anchoring might be any of the following:

- Anchoring on purchase price: this entails sticking to their purchase prices and deciding not to adopt any new decisions on that accord.

- Anchoring on historical price—for example, investors may decide not to buy a stock today because it was cheaper last year, or they may refuse to sell any asset because its price was higher in the past; and

- Anchoring on historical perception entails making decisions based on previous perceptions of the company, such as when investors decide not to invest in ITC stocks because they believe the company previously manufactured tobacco.

As discovered by Fischer and Gerhardt (2007), there is no adherence to the theoretical recommendations for addressing losing and winning assets equally and in a focused way. This is because there is a tendency that investors will likely sell the winning assets too early and keep the losing assets too long. This is what is known as the "disposition effect," as introduced by Shefrin and Statman, which is based on a combination of two cognitive errors: anchoring and loss aversion. Therefore, one of the mental errors that influences the decision-making of investors to a great extent is anchoring.

Based on the suggestion offered by Shiller (1997), the investment decisions are placed into an arbitrarily separate mental compartment, and they react in different ways to the investment depending on the particular compartment that they are operating in at the point of their decision-making. In the context of Malaysia, for instance, it is normal to see people making savings for some specific purpose, for instance, saving in order to provide the rightful education for their children, while borrowing money for some other purposes like buying cards, even in cases where the interest on the borrowed funds is higher than what they will be getting from the money they have saved for their children’s education.

Based on the statement made by Thaler (1999), there are three compartments in mental accounting. The first compartment deals with how the outcomes are being viewed and the process for making decisions, and the measures for subsequent evaluation of the decisions made. The second part deals with assigning activities to specific accounts. This maintains a record of the inflow and outflow of funds in relation to specific activities. The third and final compartment is concerned with the rate at which the accounts are being evaluated. For instance, an account can be evaluated on a daily, weekly, monthly, or annual basis. Each of these compartments of mental accounting is a violation of the economic principle of fungibility, which brings about the consequential outcomes of choices being influenced at the end of the day.

Mental accounting doesn’t just influence the personal finances of the investors; it also represents a common phenomenon when it comes to the complex world of investment. In the event that an investor purchases a new stock, the person will start to maintain a new virtual account of the stock in his or her mind. Each of the decisions, actions, and outcomes in relation to the stock are also held in that account. Such is also the case for each of the investments that have been made. Once an outcome is assigned a mental account, the impact is that it becomes difficult to view the outcome from a different angle. As a result, if the interactions that occur in different accounts are ignored, these mental processes can have a negative impact on the investor's wealth.

If these interactions among mental accounts are ignored, they can have an adverse effect on investment decisions. In contemporary portfolio theory, there are illustrations of how the combination of different assets in a portfolio of securities can reduce the volatility that comes with investing in any particular security. For instance, in the event that one class of security (taking the utility stock as a case study) seems to fall when another group of equity (for instance, oil stocks) seems to rise, the volatility associated with the risk of the investor’s portfolio can then be reduced by combining such portfolios into a single unit of portfolio. Energy stocks are impacted by rising oil prices because these companies are typically unable to recoup the costs associated with rising fuel prices as quickly.Therefore, when investors want to profit from rising oil prices, they will go for oil stocks while avoiding heavy energy users such as public utilities. In the case that the investors want to totally avoid betting on the trends in the price of oil altogether, they might need to construct an investment portfolio that features publicly traded and well-managed oil companies. In contemplating whether to buy or sell a given security, the investor's focus will be on how the returns on that security interact with the overall returns on his portfolio. The unfortunate thing here is that sometimes the investors seem to encounter difficulties with respect to assessing the interaction among different securities because they have already conceptualized mental accounting errors.

The common observation is that the investors hold onto investments that are losing value. They seem to justify this decision by offering a number of reasons, but the fact remains that they are mentally unwilling to accept the fact that they are making a loss. The common conception held by the investors is that they are only booking losses when they sell. As such, they fall prey and hold on to the losing investment with the hope that it will eventually recover its value and move towards the positive value line. This is a significant mental accounting error that exists among a number of fraternities of individual investors. Just like anything else, mental accounting has its positive and negative aspects, and the decision is left to each individual to decide what is right for his or her financial interests.

Warren Buffet, the renowned investor, stated in the 1986 Berkshire Hathaway Annual Report that: investors only attempt to be fearful when others are greedy, and greedy when others are fearful (Heller, 2000).Individual investors' decisions are influenced significantly by greed and fear.Their greed to earn a significantly high return on investment in the short run leads to excessive trading, and this is similar to their fear, which can sometimes be baseless, leading them to take decisions about buying and selling without giving much thought to the situation in hand. Thus, the interest of the investors can be hampered by both of these situations, reducing the possibility of their attaining their investment objectives.

2.4. Crafting behavioral portfolios

The focus of investors seems to be on the diversification of their goals instead of a purposeful diversification of assets. The consequence of this is that their behavioral portfolios are formed inefficiently, and these portfolios are changed on the basis of the distribution of investment objectives and the associated mental accounts. Eventually, the investor will be incurring more risk than is necessary for the level of return they expect to attain.

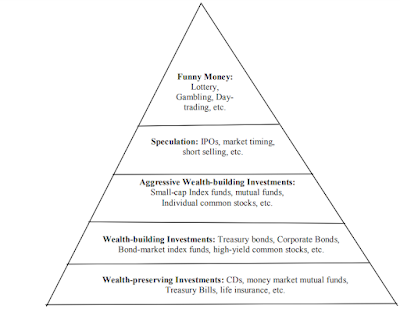

The associated psychological biases and tendencies normally result in investors thinking that their portfolio is a pyramid of assets (Hirschey and Nofsinger, 2008). Each of the layers on this investment pyramid is created with the aim of meeting specific goals (as illustrated in figure 2.1 below). Once an investor meets the objective in a given layer, the next step will be to progress to another goal with a different mental account. In order to administer the process, different investment themes or classes of assets are picked by the investors in order to match their specific objectives.

Figure 2.1: Investment Pyramid

Source: Chandra (2017)

Starting from the initial investment stage, the investor's preference is for assets that preserve wealth, such as bank CDs (certificates of deposit), money market mutual funds that come with low risks, insurance products, and Treasury bills. Once they have passed this stage and have the necessary assurance about the safety of their investment, they will now consider themselves financially and emotionally capable of taking a higher level of risk in the course of pursuing higher expected rates of return. They include investment teams that aid in wealth building in their portfolio. These investment teams that increase their ability as well as opportunity to build wealth include investment-grade corporate bonds, treasure bonds, high-yield common stocks, bond-market index funds, and a number of others. Following success in this stage, which entails having their wealth-building goals adequately funded, the investors will normally feel that they are better prepared to approach their investment objectives by taking higher risks in the pursuit of an even greater level of wealth creation. This is the stage at which they enter the aggressive investing structure, which includes small-cap index funds, common stocks, managed mutual funds, and other similar investments.Once this goal has been adequately funded, the investors eventually become emotionally and financially ready to go for a higher-risk investment, which includes speculative investment products capable of bringing about significant chances of the investors losing money. Some of the common forms of speculative investment include investing in untested companies offering their initial public offerings (IPOs), short selling, different market timing strategies, and a number of other measures. On a final note, the investors now move to the "funny money," which entails having some of their money put into gambling, lottery tickets, and day trading, where small amounts of previous winnings are bet with the full realization that they stand the chance of experiencing a complete loss. In such "get-rich-quick" strategies, investments are normally considered to be a form of recreation and not actually harmful to the emotional and financial well-being of the investors in the long run. Most individual investors, however, consider that given speculation and day trading/gambling, it is more crucial to their investment strategies.

In any case, there are two crucial issues in conventional investment decision-making that are worthy of note, which include minimizing the risk of such investments and maximizing the expected returns. These are both crucial and should be taken into consideration by the investors when they are drafting such a behavioral portfolio. Instead of putting a number of mental accounts into view and considering other psychological biases like anchoring and overconfidence together with the amount of money funded in each of the mental accounts, it is important to determine the size of the portfolio and the asset that will be allocated. As a result, how investment goals are distributed and mental accounts are associated determines behavioral portfolios.

2.5. Behavioral factors influencing decision-making in stock exchanges

The way investors behave is an area that attracts great interest from researchers because they seek to analyze the decision-making process and the factors that influence the investment behavior of these investors. Overall, the purpose of this analysis is to better target their investment choices. In the past, a number of studies have been done in this area, and there are still others that are presently conducting their research in the same area. The discussion in this section is a highlight of some of the research that has been done on this subject. As identified by Jagtap and Malpani (2011), the nature of the industry, the performance of a company, and the global exposure that a company has do influence the decision of investors to a great extent in the equity market. Dharmaja et al. (2012) came to the conclusion that most of the respondents, in relation to the behavioral factors that influence the decision-making of investors in stock exchanges, were influenced by the accounting information provided by the company and did advocate for recommendation in the least influencing group. The relationship between level of risk and the demographic factors of the investors that were confined to Rajasthan state was investigated by Jain and Mandot (2012), with Elankumaran and Ananth (2013) discovering that the factors that influence such behavior among the investors are: objective knowledge, information asymmetry, high returns, and low risk. Still on the subject, Lodhi (2014) stated that risk-taking capabilities and financial literacy have a positive correlation on the investment decision-making process, implying that an individual's financial literacy will lead to an increase in risk-taking capability.Standing on this note, the financial literacy level of UAE individual investors was assessed by Al-Tamimi and Al-Anood Bin Kalli (2009), together with other factors in relation to their influence on investment decisions, and they came up with the finding that the financial literacy levels obtainable in the region are higher than the standard desired for such purposes. This study pointed out that the investors are more knowledgeable about the pros that come with diversifying their investments, while they are less knowledgeable about financial market indices and the use of such in deciding where to push their money next. In line with this, an attempt was made by Suman and Warne (2012) to understand the behavior of individual investors in the stock market. This was done with a survey based on the collection of primary data from a sample of about 50 investors in the district of Ambala. The findings from this research show that there are different factors that influence the behavior of individual investors, such as the duration of investment, their level of awareness, and others. As discovered by Paul and Bajaj (2012), the majority of existing equity investors have a moderate level of awareness about the equity market. Their study also showed that the age and gender of these investors and their level of awareness about the equity market are not significantly correlated. In any case, there is a significant level of correlation between income and occupation and the level of investor awareness about the equity market. As such, investment in the stock market by individual investors is something that is influenced by their income and occupation. This led them to the conclusion that for the participation of retail investors to increase in the equity market, their level of awareness needed to be enhanced. In another study conducted by Kabra et al. (2010), it was concluded that the age and gender of the investors influence their capacity to take risks. Patidar (2010) also affirmed this by stating that the risk-taking capacity of investors is influenced by their age and gender, with most of the investors channeling their investment through stock brokers. In another study by Benett et al. (2011), the five factors that have huge and significant influence on the investment decisions of individual investors are their attitudes toward investing in the equity market. They include the tolerance level of the investors, the strength of the economy, the focus of the media on the stock market, political stability, and government policies towards businesses. Babajide and Adetiloye (2012) showed that there is significant evidence that risk aversion, overconfidence, framing, myopic loss aversion, and biases to the status quo could influence the investment decisions of investors in the Nigerian stock market, although these factors are not considered dominant in the market because of the low negative relationship between these variables. The resulting effect is that the value of the market does depreciate as the investors start to show biased behavior. In this study, it was concluded that being aware of the biases in behavior is the first step when it comes to making sure that the decision-making process is not adversely affected by any of these factors. Without doubt, the studies discussed above have made significant contributions to the subject matter being discussed and the field in general. But it is important to note that the findings of a research work are something that is influenced by a number of factors, such as the country where the study was conducted, the variable selected, the time of study, the method used, and so on. Therefore, generalizing the result would be difficult because different markets have different and unique features like different regulations, rules, and types of investors. As such, the focus of discussion in relation to the behavior factors that influence the decision of investors in this research will be on the three variables defined by the theory of planned behavior as attitude, subjective norms, and control.

2.5.1. Perceived risk

Risk aversion is one of the earliest definitions of risk tolerance employed by researchers when it comes to understanding the influence of perceived risk on investment decisions, and risk tolerance is considered to be the willingness of an individual to engage in a certain behavior where a desirable goal exists but the attainment of such a goal is uncertain and there is an accompanying possibility of loss if the person decides to pursue the goal (Kogan and Wallach, 1964). Still, according to early research in this field, risk avoidance, which is the inverse of risk tolerance, is defined as a stable tendency or attitude of the investor to avoid certain risks (Douglas and Wildavsky, 1982).

In the investment sphere, financial tolerance is considered to be the amount of volatility that an individual is willing to accept in the course of making financial decisions. Be it in the area of education, empirical research, or professional practice, risk avoidance is viewed as a pivotal factor that influences the savings and investment choices of people. This is because choices in relation to the allocation of asset plans, investment products, and strategies for accumulating a portfolio have all been attributed to the investor’s level of risk tolerance (Grable and Lytton, 1999).

Based on the work of Dimmock and Kouwenberg (2010), it was discovered that in cases where the investor has a higher risk aversion, the probability of the person participating directly or indirectly in the stock market will be significantly reduced. To validate this finding, another study was conducted by Lim et al. (2013) in Singapore, and it showed that there is a negative correlation between the avoidance of risk and the intention of investors to invest in the stock market. In view of that, it is proposed in this study that:

Hypothesis 1: Perceived risk, in the form of risk avoidance, will negatively influence investment decisions on stock exchanges.

2.5.2. Perceived trust

The perceived risk that the investors have about a given stock does play a pivotal role in their investment decisions in the sense that the higher the perceived risk, the more a negative attitude will be adopted, which will lead to the decision not to invest in the said stock. When it comes to defining the perceived risk, the government plays a crucial role in the development and free and fair functioning of the securities market. In the majority of countries, this role is assigned to market regulators such as Bursa Malaysia, who are tasked with supervising the entire securities market in order to increase investor trust in the Malaysian securities market.Based on the work of Guiso and Sodini (2013), the decision of investors to participate in any given market does require that such investors form a belief about the trade-off between risk and returns that one can attain by investing in such a risky asset. Another requirement is that the investors be confident in the source of information, which can come from portfolio managers, financial advisors, or the general public, as such sources are testaments to the entire reliability of the financial system. Based on the work of Calvet et al. (2009), which shows that stability is a relatively stable individual trait, this can be used to explain the reluctance or inclination of investors to take on risky assets. On the same note, trust doesn’t vary much in people across different wealth levels, so it can be used as a predominant factor for explaining why even the wealthy show limited participation when it comes to a risky equity market. As a result, the research proposal is that when investors perceive the security markets positively, it increases their chances of investing, resulting in a positive attitude toward the security in question.That is to say, a higher perception of trust would amount to a more positive attitude and an enhanced likelihood of the investor choosing a given security.

Hypothesis 2: Perceived trust will have an influence on investment decisions, where the higher the trust, the higher the intention of investors to go for a particular security.

2.5.3 Expected return

Optimism is another factor that has been extensively studied when it comes to discussions on the factors that influence investment behavior. In cases where the investors are confident that the market will continue to perform well and that the price and value of the security will continue to rise, they will likely invest in the said security. On the same note, the perceived return is normally based on solid information about the company that they wish to invest in, which is backed by sound economic indicators and is said to have a positive influence on the market. Additionally, when the investors are excessively optimistic, they might end up inflating the price of the security as they issue false indicators to other investors. Therefore, it is common for one to find that some indicators are capable of functioning on the basis of their forecasts; in cases where the investors are overly optimistic, the price of the commodity will shoot up, while negative influence will be recorded in cases where they are overly pessimistic. In view of this, numerous studies have been undertaken to understand the influence of perceived return on investment decisions, such as the works of Tariq and Ullah (2013) that were based on the Pakistani stock market and those of Tran (2017) that were based on the Thai stock market. Both studies hold that when the perceived return is higher, the investment intention will be positively influenced, and vice versa, because the purpose of any investment in the security markets is to generate returns for the investor. On that note, it is proposed in this research that perceived return will influence investment decisions on stock exchanges.

Hypothesis 3: Perceived return will influence investment decisions, where the higher the perceived return, the higher the investor's intention to invest in a particular stock exchange.

2.5.4. Word of mouth

When it comes to consumer purchase intention, the power of word of mouth has been extensively discussed. The power of word-of-mouth (WOM), whether it is coming online or through face-to-face interaction, can never be underestimated. Be it in the case of the adoption of new products, selecting between brands, or just watching television shows, word of mouth plays a significant role in the decision-making process of the consumer. However, past studies have stated that the influence word of mouth can have on the consumer does depend on the type of product in question (Park & Lee, 2009) and the trust placed in the channel of communication (the source) used to deliver such word of mouth (López & Sicilia, 2014). Based on this, it is proposed in this case that:

Hypothesis 4: Positive word of mouth will influence the behavior of investors on the stock exchanges positively.

2.5.5. Media exposure

The overall level of awareness that investors have about a given stock can be attributed to their daily exposure to the company or to other sources of exposure (such as advertisement and word of mouth, as discussed above).It has been found to have a significant influence on the purchase intention of consumers in the general market as well as the decision-making process of the investors. When it comes to media exposure, trust is also crucial because the trust that the investors have in the source of information can affect their overall trust in the brand and eventually their intention to purchase (See-To & Ho, 2014). Studies have shown that a high level of media exposure increases the purchase intention of consumers because it translates to the company being of high quality and, as such, serves as a subjective norm for the investors to choose a given company over another (Chin-Lung et al., 2013). Based on this, it is proposed that media exposure has influenced the decision-making process of investors in the stock market.

Hypothesis 5: Media exposure has an influence on the decision-making process of investors in the stock market because the higher their exposure, the higher their trust and intention to purchase.

2.5.6. Reference report

Over the years, a number of studies have been conducted in order to understand the influence of reference (financial) reports on the intention of investors to purchase stocks in the stock market, with the majority of these studies focusing on the quality of such reports. The findings of these studies have been that financial reports have a significant influence on investors’ decision-making. For instance, it was shown in the work of Fariba and Mehran (2016), which was designed to examine the effects of financial reporting on quality and investment opportunities as well as dividends on the decision-making of insurance companies in Iran. The finding from this study is that the quality of corporate financial reporting and investment opportunities have a significant correlation with dividend policy and investment decisions. Another study was conducted by Nwaobia et al. (2016), which assessed the influence of financial reporting quality on the decision-making process of investors by making use of 10 selected manufacturing companies that are listed on the Nigerian Stock Exchange, covering the periods of 2010 to 2014. It was discovered in this study that there is a positive correlation between the quality of financial reporting and the decisions of investors. In the Asian region, a similar study was conducted by Chan-jane et al. (2015), which investigated the relation between financial reporting quality and investment decisions by viewing it from the context of family firms versus non-family firms and made use of a sample of firms listed in the Taiwan Stock Exchange from 1996 to 2011. Based on the findings from this research, it is suggested that family firms are more likely to underinvest than non-family firms because they are focused more on protecting their socio-emotional wealth and that the quality of their financial reports is more negatively correlated with their underinvestment behavior. In view of this, it is proposed in this research that:

Hypothesis 6: Reference reports influence the decision-making process of investors because quality reference reports increase their chances of choosing a particular equity.

2.5.7. Financial self-efficacy

Financial self-efficacy is considered one of the factors that play a pivotal role when it comes to assessing the financial behavior of investors. Self-efficacy is considered to be the belief that an individual has about their inherent ability to organize and take a number of actions that are considered crucial for reaching a desired goal. When it comes to financial behavior, self-efficacy is related to the belief one has about the person’s ability to effect a change in financial behavior that would bring about a better outcome for the person (Danes & Haberman, 2007). Self-efficacy, which is also known as self-confidence, is considered to be a key feature in Bandura’s social cognitive theory, and it is all about the self-confidence that an individual has about their personal ability to be successful in the conduct of a given task. This belief about personal ability can aid in determining the expected results because an individual who has confidence in a given action would anticipate that the set goals of the action are attainable. Difficult tasks are viewed as a challenge to be overcome rather than a threat to be avoided by people who are confident.The person is said to have a strong interest and deeper engrossment in the activity they undertake, coupled with a stronger level of commitment towards attaining the set goals of the activity in question (Pajares, 2002). In past research, it has been demonstrated that the attitude of a person when it comes to managing has a higher mean score than self-confidence in terms of making quality financial decisions. The implication of such a finding is that an individual's self-efficacy influences their financial behavior in relation to their financial direction (Danes and Haberman, 2007).On the same note, it has been demonstrated in another study that focused on students that their financial self-efficacy has a significant and negative effect on their loan and credit behavior. The finding showed that students with a low level of financial self-efficacy are more likely to engage in unhealthy or irrational behavior toward loans (Kennedy, 2013). A similar study did show that students with a high level of financial self-efficacy and greater optimism about their financial decisions are significantly less likely to report financial stress (Heckman et al., 2014). Similar findings have also been discovered in the area of investors, where it has been made known that high financial self-efficacy results in better financial and investment decisions (Pajares, 2002), as such people will naturally take their time to reach an investment decision. Based on this view, it is hypothesized that:

Hypothesis 7: An investor’s level of financial self-efficacy has an influence on their investment decision-making process, as those with high self-efficacy take more time to make decisions and vice versa.

2.5.8. Locus of control

Generally, when it comes to a number of things in life, people make decisions under conditions of uncertainty and risk. Given that individuals' risk preferences influence their decision-making process, it is clear that any systematic change in their willingness to assume a given risk would have far-reaching implications for both socio-political and economic outcomes (Dohmen et al., 2011; Becker et al., 2012; Bonsang and Dohmen, 2015).There is also strong evidence showing that people's attitudes towards risk are related to their cognitive functioning, with the evidence demonstrating that when people have high cognitive functioning, they are more likely to go for risky investments or hold stocks (Banks, 2010; Christelis et al., 2010; Grinblatt et al., 2011).

This investment decision is influenced by factors like locus of control. What is captured by locus of control is whether or not the person considers the relationship between their personal behavior and expected reward (Rotter, 1966, p. 1). When an individual exhibits a high (also referred to as "internal") locus of control, the belief is that life outcomes are the consequences of their personal behaviors and efforts. From a contrasting view, when an individual has a low (or external) locus of control, the belief is that the outcome of their life is something that is not within their control, but instead is the consequence of external factors like luck, fate, and the actions of others (Heckman et al., 2006; Schultz and Schultz, 2016; Cobb-Clark and Tan, 2011; Cobb-Clark and Schurer, 2013).

In existing studies, it has been demonstrated that locus of control is used to explain the motivation, decisions, actions, and personal goals of an individual. To be more precise, when people have a relatively higher locus of control, they seem to show higher motivation, initiative, and productivity, which will eventually lead them to become more successful (Linz and Semykina, 2007). Considering these discoveries, it doesn’t surprise one to note that locus of control also has crucial influences on different life outcomes, which include investment choices (Osborne Groves, 2005; Becker et al., 2012). In essence, when people have a higher locus of control, they are more likely to go into the stock market and buy shares (Cobb-Clark and Tan, 2011; Buddelmeyer and Powdthavee, 2016), as they consider themselves to be in charge of their life outcomes and make conscious efforts towards attaining their overall life goals. Based on this, it is hypothesized that:

Hypothesis 8: An investor’s locus of control has influence on their investment decisions because those with a higher locus of control are more likely to purchase stocks or go into risky investments.

2.5.9: Social responsibility of investors

In the empirical context, research on the influence of investors' social responsibility on their investment decisions is novel.However, proponents of socially responsible investment (SRI) believe that SRI screenings are more than just a tool that allows investors to fulfill their moral obligation to invest.To be more specific, these supporters argue that by socially responsible investors making selective investments in firms with high corporate social performance (CSP), the firm's cost of capital will be lower, and the impact will stimulate improvement in the company's CSP.

This claim has been assessed by a number of finance-based studies that are aimed at understanding the real-world effects of SRI, but such studies are scarce, and the implication is that relatively little is known about its validity. But some of the studies in this area, like those of Chen, Goldstein, and Jiang (2007) and Bond, Edmans, and Goldstein (2012), have shown that socially responsible investors seek companies with high CSP, and as such, the corporate social responsibility performance of a company influences their investment decisions. As such, it is hypothesized that:

Hypothesis 9: Investors' social responsibility influences their investment decision-making because those that are socially responsible are likely to purchase stocks from companies with high corporate social responsibility performance.

2.6. The mediating role of herd behavior

Under normal circumstances, one would expect that investment decisions in the stock market would follow the purchase decision-making pyramid of need identification, information search, comparison of alternatives, a decision to purchase, and post-purchase actions. However, this is not always the case in the stock market (especially with individual investors), as they can just jump into purchases without following the other steps, and the main reason for that is heuristics. In literature, one of the behavioral biases that has received intensive discussion is herding. This is the propensity of an individual to abandon beliefs and information and infer them from the actions of others in the course of reaching a decision. Despite the substantial evidence pointing to herd bias as having an influence on decision-making from various market characteristics and stakes, as well as consequences such as market crashes, bubbles, and increased volatility, it is worth noting that previous research has shown that it decreases in tendency over time (Yao et al., 2014; Shantha, 2018).The implication here is that the markets could be moving towards attaining efficiency status. In any case, there seems to be a lack of literature that is focused on providing empirical evidence on the factors that are responsible for diminishing herd behavior in the financial market. What is very clear in the literature is that the investment decisions of investors are not something they make entirely on their own or something that follows a straight path, as there are different factors that influence their decisions, with many of them investing just for the sake of investment or choosing stocks based on herd behavior (Yao et al., 2014; Shantha, 2018). Individual investors typically do not take the necessary time to study and assess a stock before investing because of herd behavior; instead, they simply go for a stock based on the notion that because they performed well in the past, they would also perform well in the future; or simply because other people are going for the same stock.This view will be further analyzed in this research with primary data.

2.7. The moderating roles of attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control

2.7.1. Attitude

Based on the earlier discussions, there are different factors that influence equity holdings and the intention of investors to invest in equity products, as identified across different research in different parts of the world. In an attempt to provide a more robust explanation of these factors, these studies focus on the behavioral context, and attitude is one of them. When it comes to the influence of attitude on the decision-making process of investors in the stock market, different studies have pointed out that it has a significant influence, with most of these studies identifying financial literacy and risk aversion as two of the main aspects of investors’ attitudes that influence their investment decisions (e.g., Grable, 2003; Van Rooij et al., 2011). The elements of attitude adopted in this research are discussed below.

2.7.2. Subjective norms

Subjective norm is defined as the perception of what important peers in a group think about a given behavior, as well as the motivation of other members of the group to conform to these views (Ham et al., 2015).Based on the documentation by East (1993) in relation to the investment decision perspective, an investor’s investment intention is significantly influenced by the views of their family and friends. On the same note, the wealthier investors were found to be more interested in creating sustainable investments as a result of the positive image that society attributes to sustainable investment (Eurosif, 2012). Therefore, the expectation is that perceived public pressure will result in investment in sustainable investment projects, and subjective norms are considered to have a positive influence on the intention of investors to invest in investment opportunities considered to be sustainable (Paetzold & Busch, 2014).

Additionally, it is important to point out that subjective norms represent the combination of the perceived expectation of an important person and the intention of an individual to comply with the expectations of this important person. Understanding the beliefs of an individual can be crucial to understanding their attitude (Pohja, 2009). Another set of studies has looked at investment intention by adopting the theory of planned behavior, such as the works of Shanmugham and Ramya (2012) and Alleyne and Broome (2011). In the first, it was discovered that subjective norms are negatively correlated with the intention of investors to choose a given stock, while the second study found that subjective norms are an important predictor of investment intentions.

Pascual-Ezama et al. (2014) studied the intention of real investors to invest in a given security and came up with the finding that subjective norms have a significant influence on their intention to invest. On a similar note, another study was conducted by Mahastanti and Hariady (2014), which assessed the intention of investors to purchase financial products. According to the findings of this study, investors' decisions to purchase a particular financial product are not influenced by subjective norms and attitudes.Cuong and Jian (2014) conducted an assessment of the factors that influence the behavior of investors in a given stock market. The finding from this study is that subjective norms have a significant influence on the behavioral intention of investors to invest in a given stock market. It was found in their study that subjective norms have a significant influence on the behavioral intentions of investors when it comes to the stock market. Basically, the past results have been mixed in the sense that some have found a positive influence of subjective norms on the behavioral intentions of investors, some have found a negative influence, and some have found no influence. Based on this, the present study, based on the above discussions, is of the view that word-of-mouth, media exposure, and reference reports will all have influence on the behavioral intentions of investors in the stock market. Further discussions on these are presented below.

2.7.3. Perceived behavioral control